If, as the leader of the Family has noted, power is reliant upon invisibility, the conservative Christian organization may have just been dealt a damaging blow.

The secretive movement (known also as the Fellowship) hit the big time last week, having been dragged into the spotlight by a pair of extramarital affairs, and allegations of a hush money payment in the upper echelons of government.

For a primer on the Family and the scandals involving Sens. Tom Coburn (R-OK) and John Ensign (R-NV), and Gov. Mark Sanford (R-SC)—all of whom are connected by the Fellowship—watch the following clip from The Rachel Maddow Show. The story gained a new dimension after Maddow reported the story, when another Fellowship member, Zach Wamp (R-TN) attempted to refute Maddow’s facts, despite their having already appeared in Wamp’s local paper.

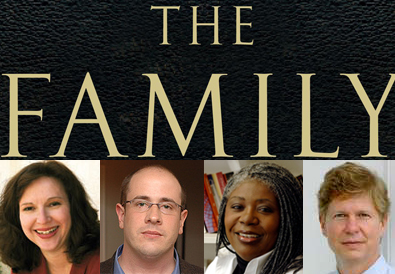

Below the clip is Religion Dispatches’ exclusive roundtable on The Family: The Secret Fundamentalism at the Heart of American Power, featuring three religion scholars and the author, Jeff Sharlet, discussing the history, theology, secrecy and future of the oldest Christian conservative organization in Washington DC.

Has a secretive, informal network of fundamentalist Christians had undue influence over American policy? Over the summer vacation, Religion Dispatches convened its first roundtable, resulting in a lively discussion of Jeff Sharlet’s new book, The Family: The Secret Fundamentalism at the Heart of American Power (Harper, 2008).

The seed of the book was planted a few years back when, after accepting an invitation to live among a group of The Family’s “brothers,” Jeff penned an article for Harper’s magazine entitled “Jesus Plus Nothing.” That experience and the article it inspired form the basis of the book, a detailed and carefully researched exploration of an informal network of powerful Christians known as “The Family,” or “The Fellowship.” In Sharlet’s words, it’s “a story of two great spheres of belief, religion and politics, and the ways in which they are bound together by the mythologies of America.”

Joining us, along with Jeff (a contributing editor for Harper’s, contributing writer for Rolling Stone, and columnist for RD) were: Randall Balmer, author, Episcopal priest, and professor of American religious history at Barnard College; Anthea Butler, assistant professor of religion at the University of Rochester; and Diane Winston, the Knight Chair in Media and Religion at USC, who has worked as a reporter for several of the nation’s leading newspapers.

Jeff’s book fills a significant gap in both scholarship and media. When it comes to the connection between politics and religion in this country, a most talked-about topic as we head into the final weeks of the election, plenty of studies have been conducted—and stories written—on everything from para-church organizations to educational institutions, but very little work has been done on elite manifestations of religion-related power.

One of the first questions a book like The Family raises is how much influence an elite cadre, such as that described in the book, can actually have on the direction of the nation.

The answer to this question, it turns out, depends on the way we understand power in a liberal society, how we conceive of the role of religion in that society, and on our reading of history.

Our discussion ranged over these issues and was punctuated, unexpectedly, by a parenthetical gesture from one of our panelists. During the course of the roundtable, a critical review of the book appeared in the Washington Post by Randall Balmer. In his closing comments, Sharlet responds to Balmer’s offstage remarks:

Ah, sour grapes! Yes, I got ’em. Not so much because Randy radically misrepresented my arguments in the Post, where I can’t respond, while offering far more nuanced arguments of his own only in this smaller and more scholarly roundtable, but because such a dichotomy represents exactly the scholarly/popular divide that allows The Family to slip between the cracks. Amongst scholars, he makes arguments that invite engagement. In the public square, he issues proclamations that do no more than police the borders of respectable knowledge, aka “conventional wisdom.”

Balmer had saved some of his most critical points for the readers of the Post, thus our discussion had a ‘sidebar’ of sorts and RD was graced with an exciting and surprise ending.

Enjoy the discussion and by all means join in.

***

Religion Dispatches: Thanks so much to all of you for joining us in a roundtable discussion of Jeff Sharlet’s new book The Family: The Secret Fundamentalism at the Heart of American Power.

The editors have just returned from a screening of James Carroll’s film, Constantine’s Sword, which does a frighteningly good job of tracing the dangers of the marriage of the Catholic church and the state. So we’re in a fairly grim mood as we begin this discussion of your book, which echoes so many of history’s most catastrophic church/state unions… But here we go:

The predominant perspective, among liberals in general, along with the media, scholars, and other intellectuals, is that through open dialogue, the airing of opposing views, and the difficult work of listening to the “other,” we will approach an increasingly just, balanced, and free society (“the noise of democracy,” as James Buchanan put it). That is to say, left and right, religious and secular (in the widely understood definition of the term), bring us to some moderate, pluralist center in which we can all live.

The Family however, describes an increasingly powerful undercurrent in the United States, which you describe as “aggressively anti-democratic,” which thrives on secrecy, reveres authoritarianism, and consists of an elite, loosely-gathered group of men steering America toward becoming a “Christian civilization” for which “theocracy” is too mild a word (Chuck Colson prefers “theocentrism”). On page 276 you write:

The Family wants to “transcend” left and right with a faith that consumes politics, replacing fundamental differences with the unity to be found in submission to religious authority. Conservatives sit pretty in prayer and wait for liberals looking for “common ground” to come to them in search of compromise.

Does the prevailing liberal intellectual view of compromise “get it” or are we missing the boat?

Jeff Sharlet: Our first (possibly) gay president’s appreciation for the “noise of democracy” has a negative echo in the thought of Family founder Abraham Vereide, who believed that religion and politics mixed best behind closed doors, away from the prying eyes of the press and “the din of the vox populi”—a pretentious little Latin phrase for the voice of the people. As Senator Sam Brownback (a man who first discovered the political advantages of The Family’s behind-the-scenes religion decades ago as an intern for Bob Dole) explains, a “God-led” politician is ultimately accountable not to the electorate, but to “one constituent.”

Guess who?

Brownback and his brothers in The Family more or less abide by the rules of American democracy, and some even believe they are defenders of its virtues. At the same time, they’re committed to a political theology that views democracy as a form of secular humanism, to which they’re deeply opposed. The kingdom of God that’s to be built here on earth, Family organizers are fond of saying, is not a democracy.

That’s what too many liberals don’t get: democracy and its corollary, pluralism, simply aren’t top concerns for many Christian conservatives—especially the elites of The Family, those whom I refer to as an avant-garde of American fundamentalism. (I view “American fundamentalism” as merging the biblical literalism and fetishism of traditional Christian fundamentalism, the belief that the “invisible hand” of unregulated markets belongs to God, and a vision of American empire.)

Too many liberals put their faith in a mythical center, a set of values shared by all. Their commitment to this center is so great, in fact, that they’re willing to travel any distance to get there. That’s what Christian Right leader Chuck Colson understood when he wrote that he loved “dialogue” with liberals because he simply had to hold his ground and wait for them to come to him.

Consider, for example, some of the achievements of our last “liberal” administration: a “free trade” pact deeply opposed by working people; the partial privatization of welfare; and the passage of a “religious freedom” act that allows conservative evangelicals to influence foreign policy according to their analysis of other faiths’ religious customs. Each of these projects had been long dreamed of by the avant-garde of American fundamentalism. That’s not to say that The Family are puppetmasters, pulling invisible strings; rather, The Family is first and foremost an ideological project bent on setting the very terms with which we consider “democracy,” social justice, and freedom. And in that regard, they’ve been tremendously successful. The center slouches rightward, and nobody remembers that it was ever otherwise.

That’s why I think history is one of the most important weapons progressives can use to fight the slow but steady accretion of imperial customs. Compromise is a forward-looking endeavor. But you can’t honestly compromise if you don’t know what you’re giving up. Liberals won’t “get it”—the “it” being the influence of American fundamentalism—until they remember what they’ve already given up: organized labor as a pillar of democracy rather than an increasingly irrelevant special interest; the social gospel of social justice as a main strand—maybe the main strand—of American protestantism; a vigorous, often militant activist rank-and-file with deep roots in black churches, the left flank of the Catholic church, and the “peace churches”; and, maybe most importantly, a prophetic voice, a voice that speaks truth to power, against power, rather than seeking power.

How do liberals, leftists, and other progressives reclaim those foundations, that prophetic voice? The first step, I think, is a long, hard look at how they were lost. That means looking backwards before we can look forwards. It means facing the painful truth that what many of us considered a “moderate, pluralist center,” was, in fact, a political establishment—that Camelot was a layover on the way to Vietnam.

And, that the great thing about democracy isn’t moderation or anything so milquetoast as a “center” but rather its “noise,” as Buchanan put it, “the din of the vox populi,” pooh-poohed by The Family. I love that din, a ruckus of sharp words, sharp elbows and strong ideas. American fundamentalism preaches harmony and unity, not just one God but one ideology, and, ultimately, one ruling class. American democracy, I argue, should be a cacophony.

The irony is that fundamentalist intellectuals came to a deeper understanding of that noise during their long years in the cold. Populist fundamentalists recognized that the ostensibly moderate center excluded them, even suppressed their views, that the public square wasn’t so public after all; elitist fundamentalists saw that establishment liberalism wasn’t so liberal after all, either, and that at least two-thirds of their vision—free market fundamentalism and American imperialism—could be realized whether the party in power was Democratic or Republican.

So let’s forget about “theocracy” and “theocentrism”; let’s concern ourselves not with what fundamentalist ideologues say they want, but with what American fundamentalism has already achieved. Only when we understand that, I think, can we seriously consider “compromise” and the construction of the kind of public square dreamed of by liberalism.

Randall Balmer: I’m perfectly willing to grant that the aversion to organized labor that marked The Family’s origins, the weakness for dictators and the “baptism” of free-market capitalism make for a less-than-attractive picture, but I worry that Jeff has painted this movement with far too broad a brush. Let’s remember that such distinguished liberals as Mark O. Hatfield and Harold E. Hughes were closely associated with The Family; they hardly fit this profile. I have no brief whatsoever for the politics of Brownback or Inhofe or Colson. Although it’s certainly fair to assert, as a generalization, that The Family’s politics tilt toward the right, there are important exceptions—Tony Hall also comes to mind—to this generalization.

All of this leads to an important consideration. The author parses this group as a political movement, but that scheme (as I suggest above) doesn’t hold. What if he looked at The Family as a religious movement instead, as I think it is? Seeing it as a movement of religiously conservative individuals, rather than defined by its political conservativism, allows us to account for people like Hall and Hatfield and Hughes. I’m also uncomfortable with the blithe conflation of evangelicalism with fundamentalism. These two movements, although related, are, in many important ways, distinctly different (as Jeff knows). Mark Hatfield, for example, is no fundamentalist, and there are few more articulate defenders of the First Amendment and the separation of church and state.

In the interest of full disclosure, I should mention that during the summer of 1975, when I was an intern for the House Republican Conference (I was then, as I am today, a Democrat), I lodged in a sorority house that The Family had rented on the campus of the University of Maryland. The residents there, as Jeff suggests in the book, spoke the name “Doug Coe” in hushed, reverent tones, but I don’t recall that he ever visited that outpost of his empire.

Diane Winston: Immersed this summer in reading about the 1970s, I take your point, Jeff: We need to know our history. How, when and why did we lose the culture war? …which, as you correctly note, was less about sex and family than politics, economics and theology. I could argue that the turning point was Vietnam, the 1968 election, Watergate, the Arab oil embargo or Roe v. Wade. I could even blame it on Jimmy Carter and the killer rabbit. But for our purposes, here and now, I want to start with the demise of the protestant mainline denominations.

When did we stop looking and listening to mainline leaders? For the first half of the twentieth century, many of these men and women—often in concert with, supporting and supported by progressive Catholics, Jews and progressive church leaders—spoke truth to power. Their priorities differed as much as their theologies. But Dorothy Day, Reinhold Niebuhr, Mary McLeod Bethune, Abraham Joshua Heschel and their ilk all acted on the belief that doing God’s work began by serving justice.

This vision had already gone awry when Martin Marty, writing in The Christian Century in 1973, sought a new role for the church in a “suddenly different world.” Marty diagnosed the problems that faced the church at a time of social dislocation and called for a mix of humanism and prophecy—witness for God and responsibility to creation—as a way forward. Noting the trends toward personal experiential faith in religion and “security-seeking” in society he surely understood he was bucking the times. Yet even he could not (fore)see the rise of the type of fundamentalism that you describe in The Family.

Emanations from that fundamentalism helped to delegitimate the mainline although some of the problems were self-inflicted. The tendencies that Marty enumerated were inadequately addressed, and the gap between leaders and followers grew wider. People in the pews wanted a faith they could feel while denominational leaders seemed preoccupied with overseas struggles for liberation.

What, then, was cause and what was effect when the conservatives charged mainline leaders of arming Marxist guerrillas, a story that the mainstream media repeated and repeated and repeated? Was the mainline sidelined by its own ineptitude, by a right-wing conspiracy, by an echoing press or all the above? Even so, why has no one been able to offer an alternative? Do ineptitude, misinformation and narrative constructs still keep us divided? (After in-depth readings of the The Christian Century, I know I owe old white guys a big apology. I now need to reconsider what I think I know about organized labor, feminists, peace churches, etc.)

You say Camelot was a “layover on the way to Vietnam.” Maybe so, maybe not. On June 10, 1963, President Kennedy delivered the commencement speech at American University. In the middle of the Cold War, he laid out his vision for a world at peace and how we might get there:

“Some say it is useless to speak of peace or world disarmament, and that it will be useless until the leaders of the Soviet Union adopt a more enlightened attitude. I hope they do. I believe we can help them do it. But I also believe that we must re-examine our own attitudes, as individuals and as a Nation, for our attitude is as essential as theirs… First examine our attitude toward peace itself. Too many of us think it is impossible. Too many of us think it is unreal. But that is a dangerous, defeatist belief. It leads to the conclusion that war in inevitable, that mankind is doomed, that we are gripped by forces that we cannot control. We need not accept that view. Our problems are man-made; therefore, they can be solved by man.”

It’s instructive to read that speech with the knowledge of how subsequent presidents have spoken about our political foes and our capacity, as individuals and as a nation, to affect change. What if we heard that speech today?

Anthea Butler: Jeff, thinking about your closing statement that it’s not about what fundamentalists say they want, but what they have already achieved; that’s precisely what this is all about. The means of achieving it comes from a quiet, upper-class organizational structure like The Family, while everyone else is watching the sideshow of preachers and abortion protesters. The vox populi voice of fundamentalists, whether Jerry Falwell, or John Rice, was not the kind of voice someone like [Family founder, Abraham] Vereide wanted. Those voices were “lower class,” who could appeal to the masses. While those voices were distracting some of the public (and later used to effectively distract both the mainstream media and the political pundits) The Family was able to deal across both sides of the table to any politician that came its way in order to get to their higher good of a “kingdom,” ruled by “kings.” Their pragmatism knows no moral boundary, to be sure. And they certainly understand history in a different way, but they understand it. And that’s the major issue.

Leave it to Diane, however, to bring up a killer rabbit (lol). But you know, fundamentalist Christianity has been a killer rabbit of sorts, eager to swim up to the boat; but no one really knows if its just crazy, rabid, or looking for something to eat. One thing that rabbit does have is some history to act upon. It knows if it at least swims up to something, chances are there will be some type of engagement. That rabbit knows it needed to eat, and got plenty of food with Roe v. Wade, ERA, and the sexual revolution. The liberals (or liberal Christians, because I can’t blame a garden variety liberal for not knowing these FCs [fundamentalist Christians] existed), couldn’t even see the rabbit coming at them.

While off the public radar, the important work of the FCs was in structure put into place post-Scopes [“monkey trial”], para-church organizations, Bible schools, and other religious institutions. Their emergence onto the the public scene in the 1970s and beyond was a conflagration of culture, technology, organizational skill, and purpose; all things which served The Family well. In that maelstrom, what liberal could see what was to come? Finally, I think Harvey Cox’s The Secular City helped, as much as all the rest of the upheavals of the 1960s, religious studies folks and others forget that religion, especially fundamentalist Christianity, existed. By buying into the secularization thesis, the prophetic voice was lost. Who needs a prophet when there are no souls to save, or no apocalypse to come?

JS: I think we can all agree that it’s long past time to put the secularization thesis to bed. Anthea has identified a promising alternative: the “killer rabbit thesis.” This bunny—a fundamentalist tradition that evolves, as it were; one that doesn’t “come out” of the world, as early fundamentalists once spoke of doing, but rather paddles around, seeking engagement—this bunny is, indeed, a dangerous character. Why? Because fundamentalism recognizes the parameters of democracy, and, for the most part, operates within them—but in pursuit of anti-democratic ends. This is one of the problems of democracy that mainstream liberals have proven incapable of addressing.

I call it the Algeria Problem. I happened to be in Algeria in 1992, the day the Algerian military rolled out its tanks to roll back the electoral victories of a party called the Islamic Salvation Front. On the one hand, I was glad for those tanks; it was the big gun positioned outside of my hotel that kept a rabble-rouser who was preaching against Americans—against me—on the other side of the street. The Islamists had popular support; the military had guns—and the tacit support of Western democracies. When I returned home to the US, I was stunned to learn that inasmuch as Americans had heard of what was going on in Algeria, they heartily endorsed the military coup that prevented the Islamists from coming to power. It wasn’t that their commitment to democracy was shallow, but rather that they couldn’t even imagine radical Islamists—“fundamentalists”—winning fairly in the democratic arena.

Algeria, 1992 is one of those stories for which the old labor standard, “Which Side Are You On?,” really doesn’t apply. Having witnessed firsthand the pro-secularism military’s tank tactics, I couldn’t for a moment believe they were genuine defenders of democracy. The Islamists were entitled to their electoral victory. But that didn’t mean one had to like it—it was true that they intended to do away with many basic civil liberties. This leads us to the Algeria Problem: liberals who enjoy the benefits of establishment power don’t recognize as democratic the challenges to their authority that emerge from populist fundamentalist movements. Consequently, they don’t develop a real democratic response. They dismiss fundamentalism’s challenge as “fringe,” until one day they wake up to discover it at the center of things, and they discover that they have no honest grounds with which to oppose it—so they fall back on establishment power and tradition.

In the worse case scenario—Algeria, Turkey, even, to some degree, France—that leaves all the political energy in either the hands of anti-democratic fundamentalists who use the levers of democracy to pursue power, or an anti-democratic establishment using the rhetoric of democracy to hold onto power.

Let’s talk about the former first, the anti-democratic fundamentalists who use democratic methods—Anthea’s killer rabbit, the strangely swimming bunny that almost bit Jimmy Carter in the middle of a lake. Looks like a bunny, swims like a—hey, wait a minute! Rabbits can’t swim! That’s our clue that this killer rabbit is a hybrid, part bunny, part shark. Which is to say, sort of like the fundamentalism that sought power post-Scopes trial by building up a social movement of para-church organizations, educational institutions, and, most understudied by academic scholars—an elite cadre, best exemplified by The Family. This American fundamentalism looked like a democratic bunny—they built schools, they organized, they elected their champions to office—but it swims like a shark, seeking anti-democratic ends: restricting the free exercise clause of the First Amendment, ignoring the establishment clause altogether, and supporting an imperial vision of American power that imposes its hybrid-version of American democracy/American gods around the world through support of dictators considered “men of God” (Haiti’s Papa Doc Duvalier, for whom Family members arranged congressional support, Efrain Rios Montt, the Guatemalan killer championed by Pat Robertson, etc.).

That, sadly, is the link between the killer bunny and its ostensible victim, fundamentalism and the establishment. What we learn through The Family is that when it comes to the question of American democracy vs. American empire, fundamentalism and the establishment, even the liberal establishment, are on the same side. Which side are you on, indeed—are you a fundamentalist, or a liberal? And what difference did it make to Vietnam in, say, 1965? Or Somalia, in 1984, when fundamentalists, Republicans, and Democrats teamed up to arm one of the 20th century’s most bizarre killers, Siad Barre? Or Somalia, right now, as American bombs fall on the remnants of a popularly-supported Islamist movement that nearly brought stability to the nation for the first time since Barre reduced it to rubble with American bombs?

I can imagine Randall’s response: This is politics, not religion. Or maybe the other way around. But the three men he cites as “good” members of The Family— Senators Mark Hatfield and the late Harold Hughes, and Representative Tony Hall—are perfect examples of how religion and politics, and, in this case, fundamentalism and liberalism overlap. (A quick word on “fundamentalism” vs. “evangelicalism”: in the introduction to the book I explain my usage of fundamentalism, qualified by “American,” as more accurately descriptive of a religious movement that includes some but not all evangelicals, a few but not many mainline Protestants, and even some Catholics, such as Senator Brownback—all bound by a commitment to the idea that they can have Christ without religion, faith without history, and power without blood.)

Senator Hatfield, a Republican from Oregon, opposed the Vietnam War; good on him. At the same time, he provided Nixon with memos listing Family assets around the world, “key men” who could be used for back-channel politics. One such was the prayer group of Indonesian parliamentarians The Family organized around the oil-rich, anti-communist Indonesian dictator Suharto, who they predictably declared a “man of God.” Suharto, a Muslim who prayed to the American Jesus when Family politicians and oil execs came around, then killed half a million of his own citizens. So what is The Family’s response—at least he prays.

One Family organizer who prayed often with Suharto reported back to congressional members of The Family that the dictator had exclaimed of The Family’s soft-sell American fundamentalism, “In this way we are converted, we convert ourselves—No one converts us!” A Family associate, trying to defend The Family’s long support for and aid to Suharto, asked me whether the killing took place before or after Suharto formed his alliance with The Family; the answer, sadly, was before, during, and after. Suharto never stopped killing. But Mark Hatfield, that distinguished liberal, saw Suharto as an opportunity. One might say I’m being naive, that American power must make deals with the devil. I’ll grant that; but which devil? And on what terms? The elite fundamentalism exemplified by The Family has blinded even the best-intentioned among us to those questions.

One such example is former Representative Tony Hall, a Democrat from Ohio who through his involvement with The Family became anti-abortion and anti-queer, a friend and legislative supporter of the Dobsons, and one of Bush’s only new Democratic appointees during his first term. Bush made Hall, who genuinely cares about world hunger, ambassador to the UN for food issues, a subtly powerful position which he used to become an aggressive champion of biotech giant Monsanto, urging the overthrow of democratically-constructed barriers to GM food in poor nations. Food First, an NGO dedicated to the idea that democracy and food go well together, calls Hall’s work “’poor washing’—an attempt to confer legitimacy and prevent debate over a policy by making the spurious claim that the poor will benefit from it.”

Last, and sadly, least, Randall’s other “distinguished liberal,” the late Senator Harold Hughes, a Democrat from Iowa. “Distinguished” might be a stretch—Hughes’ unedited memoir, available in The Family’s archive—reveals that he arrived at the conservative Christianity of The Family only after ESP and alien encounters had failed him. But “liberal,” for the most part, yes—Hughes was a far more ardent foe of the Vietnam War and a champion of various Great Society programs even as they eroded in the ’70s.

But, through The Family, he also became a champion of Ferdinand Marcos, the Filipino dictator for whom he helped organize a National Prayer Breakfast, and Chuck Colson, the Watergate felon who, with Hughes’ help, built a massive Christian Right organization and became American fundamentalism’s “house intellectual,” in the words of his admirers. Colson, remember, was the man who wrote that he merely needed to hold his ground and wait for liberals to come to him. In his bestselling memoir, Born Again, he writes that within days of his first prayers with Hughes and The Family he discovered a “veritable underground of Christ’s men all through government”; former enemies such as Hughes who now pledged their friendship and support. In a June 11, 1974 letter to his parole board—asking for early release to work with Hughes and The Family, under their supervision (which was granted)—Colson wrote: “That which I found I could not change or affect in a political or managerial way, I found could be changed by the force of a personal relationship that men develop in a common bond to Christ.”

That which he could not achieve through politics, he could achieve through the spirituality of The Family. Colson, like Abraham Vereide and Doug Coe, Vereide’s successor as leader of The Family, became an admirer of Hitler. Wait—not of Hitler’s ends, but of his means. And what does that mean? Genocide? Purges? Kristallnacht? Of course not. The “Better Way,” as Vereide described the lesson of Hitler in a pamphlet distributed to his congressional disciples in 1948, was the unity and harmony of Hitler Youth, in which Hitler’s followers learned to work together in total agreement. Coe makes the same point, arguing that among the leaders of the 20th century who best understood what he views as the New Testament’s primary message of unity were Hitler, Stalin, and Mao. Evil men, he’ll add when pressed, but effective!

In a clip from a sermon to evangelical leaders you can see online via NBC News, Coe offers, as an example of a friendship to be emulated, that of Hitler, Goebbels, and Himmler. “Just a metaphor,” says Family defender David Kuo, a former special assistant to President Bush, widely respected by liberals for his later turn against the president. Some metaphor. But remember, it’s the methods, not the ends, to be copied. Here’s how Colson once put it in a letter to Coe, upon meeting a group of West German Family politicians, some of whom were likely involved in the joint American-West German effort to arm up the Somali dictator Siad Barre, a self-described “Koranic Marxist” who agreed to pray to the American Jesus in return for weapons with which he promised to fight communism (is this a matter of ends, or means?): “It is a fabulous group of men,” wrote Colson. “In fact, I’ve never met any group quite like it. I think we should arrange to use them as a model for leadership groups around the world. We’d better do it in a hurry, however, before they lead the next Nazi takeover out of Germany.”

What do we call that? Religion, or politics? Ends, or means? A metaphor for friendship, or a theology of power? Was the Colson/Hughes alliance—which resulted in the blueprint for faith-based initiatives and the partial privatization of welfare—an example of fundamentalism or of liberalism? Hughes, who retired from the Senate to work full time for The Family, is long gone. Colson, part bunny, part shark, the quintessential killer rabbit, remains at the heart of power decades after serving prison time for his attempts to undermine democracy.

Let me attempt to restate the Algeria Problem: Liberals see the ends of fundamentalism as anti-democratic, and so assume that fundamentalism’s means are also anti-democratic. But liberals see the ends of the establishment as, basically, democratic, that “moderate pluralist center” with which we started this conversation, and so assume that the establishments’ means are democratic, too. The result? Fundamentalism and establishment liberalism, ostensibly opposed, lean against one another, two sides sustaining one another, forming a steeple—the temple of empire in which we sacrifice democracy, with the best of intentions all around.

Closing irony: A series of memos flew around The Family’s leadership following the 1965 publication of Harvey Cox’s Secular City.

Brilliant! They declared. An opportunity, all agreed, for the killer rabbit to get in the water and start swimming.

***

RD: I’ve been gently told, much to my surprise I have to admit, that not everyone assumes that America is an empire as I, and others in this RT have noted without qualification.

Writers and thinkers across the political spectrum (and for many decades now) refer to America as an empire (whether it’s Georgetown scholar Charles Kupchan, warning of the inevitable fall of empires in 2002’s The End of the American Era, the Times’ Michael Ignatieff on the burden of empire, or Niall Ferguson suggesting lessons from the British Empire—there are others) some would disagree either that we are an empire, or at least that we’re an empire in any recognizable historical sense.

So, given the fact that The Family itself seeks to cast America as an Empire of Christ, and that The Family sees America as an empire, it’s worth asking: is America an empire? Why? And: Is this a bad thing?

AB: In my opinion, the only way you could classify America as an empire right now is that the nation is an empire in decline. I personally don’t believe America is an empire, for many reasons, but especially with a president with low approval numbers, a failing war, and a decrepit infrastructure.

Organizations like The Family and fundamentalist Christians, however, see an “Empire of Christ” at the core of any definition of “empire.” Their earnest, methodical recasting of the narrative of American history has been envisioned through the lens of Godly founding fathers, one nation under God, and the like (see Jeff’s article in Harper’s “Through a glass, darkly,” for a great exposition on how Christians are homeschooling their kids with this narrative). No matter if the empire is in decline, the declension can always be blamed on the “unbeliever,” nontraditional Christian values, and the like. What is intriguing about The Family however is that you need to have a firm understanding of empire in order to go after the “elite leaders.” Leaders need to run something (empires), or be able to influence those who do, in order to have value. In that scenario, it doesn’t matter if the leadership is bankrupt, as long as they pray (e.g. our current president), are in charge of a country or decision making, and pledge an allegiance to Jesus. The fall of the empire, or rise of it, can always be attributed to Jesus, and that way The Family is absolved of having to deal with the messy question of good, bad or failing empire. It’s all about business, 24/7.

Perhaps the business model is the most controversial way to think about the term “empire.” America as the purveyor of “popular culture” and capitalism puts it squarely in the empire business. The idea is already firmly entrenched around the world. American brands can be found everywhere, and the television shows and media are available to all. Perhaps that’s the real empire of America after all, a virtual lock on media and aspirations to American values, whatever those may be.

Oh, and just so you don’t think I am insane with the business model of empire, this post on DailyKOS is exhibit A. Rather long, so if you don’t have a lot of time, just watch the first ten minutes or so of this, and you’ll see what I mean. This was was scheduled to be rebroadcast on TBN over the 4th of July weekend over protests from the Military Religious Freedom Foundation.

DW: Thanks, Anthea, for the links. It’s a good story, especially in the wake of recent coverage of [religious persecution at] the US Naval Academy.

I was thinking about empire last night, too—but as your final comments suggest, the United States is less an empire in the classic sense than a hegemon that “controls” culture through media. Even if the media is not religious per se (Ironman as opposed to Carman), its values and ethos still reflect free-market capitalist Christianity.

It’s not surprising, then, that “radical” Islam, an alternate religious hegemon, would push back. (We can argue whether “radical Islam” is less about religion than politics after we decide about our religio-political discursive system.)

My point is that our enemies see what many of us in the knowledge industries overlook—the religious underpinning of the American brand (to return to Anthea’s business model). This is why The Family can operate under the radar, and why Jeff’s analysis isn’t front-page news. The knowledge elites believe in church/state separation as a matter of faith. But it’s their reality and it’s not necessarily shared by folks who listen to Carman or who idolize Doug Coe.

Until the media understands this, the threat that The Family poses won’t sink in. So—how do we interrupt business-as-usual and provide an alternative to the reigning narrative?

JS: The single most valuable point made in Empire, the paradigm-shifting argument by political theorists Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, is that the days of what might be called hard empire—enforced occupation armies and viceroys and gunboats—have given way to a form of soft empire that “presents itself not as a historical regime originating in conquest but rather as an order that effectively suspends history and thereby fixes the existing state of affairs for eternity.”

We might argue with much in Hardt and Negri’s broader diagnosis—their almost total neglect of religion, for starters—but this is a construction that could have almost come from the mouth of Abraham Vereide, founder of The Family, himself. Vereide preached his hybrid faith of Christianity, capitalism, and Americanism as “the universal inevitable,” and as early as 1948 described a coming era of corporate globalization he called, with enthusiasm, “the age of minority control.” Jesus—the businessman Christ of avant-garde fundamentalism, that is—would be, he believed, the only transcendent “message” capable of uniting the various leaders exercising minority control. In that regard, he was wrong: finance still reigns supreme over faith.

Or maybe, as I understand Diane to be suggesting, the two—faith and finance—are more intimately linked in the eyes of those who don’t share either with American capitalism. “Our enemies,” Diane writes, “see what many of us in the knowledge industries overlook—the religious underpinning of American hegemony.” The enemies of empire speak often of the crimes of the past (sometimes, unfortunately, only to obscure their own). Empire, particularly the religiously mediated media empire embraced by The Family, tends to favor the future—but only rhetorically. The soft empire that evolved from the mean old empires of conquest promises: The future is now. That’s the promise implicit in the theological globalism of The Family, an ahistorical faith that literally fixes—in the old Tammany sense—the existing state of affairs, “for eternity.” Imagine eternity, though, not as an expression of time but as an entity; a deity; a concept of authority; Boss Tweed with a halo and a Harvard MBA.

***

RD: Let’s talk about the ubiquitous question debated by pundits, pollsters and journalists of whether “the religious right is dead.” Or not. I suspect that the formulation of the question is entirely wrong, but we’ll leave it up to you all to discuss that.

More specifically, and related to The Family; I saw FitzGerald’s New Yorker essay on Joel Hunter and the other “broad spectrum” megachurch leaders as the latest in a series of liberal or secular media reading the reduction in the number of evangelicals who will pull the “R” lever (and the addition of poverty, the environment and war to the greatest hits of abortion and gays) as perhaps auguring the “end” of a damaging force in the American political system. Those who favor this narrative tend to see the religious right as having been “born” of Roe v. Wade, feeling its adolescent oats during the Carter administration and reaching maturity with the election of Ronald Reagan.

After reading The Family, however, with its insistence that it’s less about “R” or “D”, liberal or conservative; that it is, in fact, specifically not about that, I was left wondering whether this shift does in fact signal the “end” of something (the religious right) or whether this is merely a shift in the visible form of it; of the earlier Hardt and Negri quote which, as Jeff pointed out, could just as easily have come from the mouth of Vereide: “[empire] presents itself not as a historical regime originating in conquest but rather as an order that effectively suspends history and thereby fixes the existing state of affairs for eternity.”

RB: This line of questioning does, in fact, get us into the uses—and misuses—of history (which, I suppose, brings up Jeff’s use of Jonathan Edwards and Charles Finney as “fundamentalist” precursors). More to Evan’s point, however, the widespread acceptance of the abortion myth tends, falsely, to skew the analysis of the religious right along a political axis. If you look at the true origins of the movement, on the other hand, it becomes clear that, whatever sleight of hand was pulled off by the leaders of the religious right, the movement finds its resonance in deeply felt—if unacknowledged—sentiments. And now that abortion has somehow insinuated itself into the “moral” consciousness of religious right types, it will be much more difficult to dislodge than the pundits think.

I do think that Frances FitzGerald is correct (along with many others) in heralding a shift in evangelical attitudes, although she misses some of the nuances. First, it’s not really accurate to lump Ron Sider with Tony Campolo and Jim Wallis. Yes, he was once in that camp, but he abandoned the cause some time ago (and long before the 2004 election); his latest book, The Scandal of Evangelical Politics, is really a disappointment to those who once regarded him as a moral leader. Second, I think the generational dynamic, though mentioned by FitzGerald, is even more significant than she acknowledges. The younger generation of evangelicals, though they claim to be “pro-life,” has grown weary of what passes for the abortion debate. Issues of sexual identity, moreover, simply don’t compute with most of them, whereas the environment is a pressing issue, the protests of Chuck Colson, James Dobson, and Tony Perkins notwithstanding.

The temptation to understand all this through the lens of partisan politics is almost irresistible. The Family points us beyond that (though Jeff once in a while falls back into that trap himself, when he identifies someone as a democrat and remarks that his affiliation provides some political balance).

AB: Picking up on Randy’s observation that this is a generational issue, I agree entirely. I think for the younger generation of evangelicals (I think this might extend even up to 50-year-olds, but that may be stretching it a bit) these polemical tirades about gay marriage and the like are wearing and repetitive, when more pressing issues like economic injustice, the environment, and right to life issues for everyone (not just an embryo) are stark.

What does irritate me, though, is the perception that evangelical means white. There are evangelicals of color who never fit into this old, white male bastion of blustery rhetoric, and they have had to wrestle with moral issues of their respective communities in different ways than the cabal of folks residing in Colorado Springs. That group has always been about another agenda, although they did get co-opted somewhat in 2004 election.

Is the right wing dead, however? Not quite. I would make a case for Jerry Falwell and others galvanizing the rhetoric so much so that all of our mainstream media now positions themselves as a modern day Cotton Mather in the Salem witch trials, eager to harangue those who differ from the mainstream. The position of both attack and besiege has played well for their groups; it just couldn’t last when they finally got what they wanted, a president who seemed to have a faith like their own. I would love to get all of the “old guard” in a room and ask them how it feels that their most Christian president is also probably going down as the worst president ever. That’s a commercial for evangelicals to stay away from politics if I ever saw it. Being pimped by Karl Rove for votes can’t make them feel too powerful right now.

Maybe the smartest thing about The Family is that they don’t have any qualms about dealing with non-Christians to achieve the goals that they want. It is certainly easier not to have to pay lip service to the supposed power brokers when you can get to individuals who really have power, and offer to help and pray for them and with them.

DW: Sorry to sound like a broken record, but since more Americans follow the news media than read history, I want to ask again about interventions. The religious right is not dead as long as the legacy media keeps it alive. The New York Times, et al., wants it alive; it’s great copy. Likewise abortion. Even if it’s actually a case of false consciousness, it remains real and contested—thanks to to the media and to those who care deeply.

How do you change the focus of this religio-political discourse in a way that makes sense not only to evangelicals who are truly upset about “abortion on demand,” but also to pro-choicers, for whom this is also a defining issue? And while sexuality may be a generational issue, I am less certain about abortion. Abortion may not be the issue for 20- and 30-year-olds, but it’s among a constellation of concerns.

Also, what is The Family up to next? And how might we use new media to challenge its next narrative? Is Anthea suggesting that we start guerrilla groups among Christians of color, Jews, Muslims, Buddhists, Hindus, nones, and others? The Internet makes alternatives possible in ways that were not available five or ten years ago.

JS: I’ll start by taking Randy’s bait on the uses and misuses of history because I think we can learn something about the present moment of apparent evangelical transformation by reviewing our history of revivals. I chose to position Jonathan Edwards, chief author of the First Great Awakening, and Charles Finney, spark of the second, as precursors to fundamentalism (not, as Randy writes, fundamentalist precursors) because A) the people I write about in the 20th century saw them as such; and B) they both undermine stereotypes of evangelicalism. Look at Edwards: he was fascinated by almost everything, capable of grasping almost any idea he encountered; quiet, intense, hardly a pulpit-pounder—not a man interested in pompous authority. Imagine how today’s media might cover him. Stephanie Simon at the LA Times might declare him a “New Monastic,” at odds with the social authority of the old Christian bigs; Frances FitzGerald would surely be impressed by the breadth of Edwards’ intellectual interests and announce him to New Yorker readers as a “new evangelical.” Lesser journalists would take note of Edwards’ emphasis on natural science, on Newton’s Opticks, and herald a trend in American evangelicalism as Christianity remakes itself for the bold new world of the 18th century.

And all these stories would be correct; indeed, they are, more or less, correct when applied to American evangelicalism today. But the press gets it wrong when it assumes that these trends spell the end of the religious right. Rather, they mark the transformation of the religious right—its expansion, even, as the movement grows more intellectually sophisticated. The issue preoccupying the brightest religious right intellectuals, for instance, is not abortion, it’s male authority—a broader agenda. Bestselling books such as Wild at Heart and Every Man’s Battle go far beyond opposition to queer rights; rather, they’re assertions of a purified straight identity, a manhood purged of anything feminine. Consider the young purity crusaders I write about in chapter 13, “The Romance of American Fundamentalism.” They’re smart, hip, engaging kids; they scoff at the old Christian Right war chiefs, they live in Brooklyn and worship in Manhattan, they don’t like Bush—and they’re dedicated to an ideology that in its emphasis on “purity” above all is potentially farther right than anything Bush has ever dreamed of. It was the late Francis Schaeffer and his son, Frank, who persuaded evangelicals to make abortion a top concern. But they never saw abortion as the endgame; rather, they meant it as a wedge, a symbol for secularism. Eventually, they hoped, the next generation of evangelicals would move beyond limited fights about moral matters and develop a broader critique of secularism itself.

Here we are—the Joshua Generation, as some on the right (and, now, the Obama campaign) call it, the total fundamentalism of The Family’s “Jesus plus nothing” trickling down from the elites and the intellectuals of American fundamentalism to the masses of mainstream evangelicalism—white, black, Latino and Asian. (The kind of racial “reconciliation” that seeks a unified movement particularly of black and white evangelicals is, I’d argue, the result in part of the elite religion of The Family, which always saw racism as an annoying distraction from the larger task of spiritual purification. Anthea notes that The Family never has qualms about dealing with non-Christians or the “wrong” kind of Christians; the same might be said of their approach to race. Doug Coe, considered a racist even by some of his friends, never had qualms about dealing with black leaders such as Papa Doc Duvalier or Siad Barre, or, for that matter, more mainstream American leaders such as Andrew Young. He recognized their power, and was willing to deal with them as equals. Mighty white of him.)

To Diane’s point that the press is keeping the religious right alive: I’d say the media is keeping it under wraps, by reporting on stylistic changes and the broadening of the religious right’s agenda as a liberalizing force. This is the anti-right bias conservatives complain about, and on this score, they’re correct—the press conflates the right wing with narrowness, rigidity, and obsession, and liberal ideas (but not left ones) with broad-mindedness, flexibility, and growth. Sometimes it gets even dumber than that—Randy’s right about the temptation of the partisan lens (though, for the record, I’m the last person who’d consider the addition of a Democrat to a Family cell as “balance”; rather, that’s the narrative The Family is selling its members). There’s a sense here in which the media’s paradigm for political and religious ideas is undermining it—I think Diane’s right that any smart media organization wants to keep conflict alive, and to that end they find the religious right very helpful. But, having identified certain issues—global warming, poverty—as fundamentally liberal, they’ve backed themselves into a bland, one-sided story in which we all become spiritual, green, and “newly” traditional.

***

RD: Last question—as a series of ideas and statements:

“That which I found I could not change or affect in a political or managerial way, I found could be changed by the force of a personal relationship that men develop in a common bond to Christ.”—Charles Colson, author, founder of Prison Fellowship and Watergate felon

Religion or Politics? It’s come up a number of times both in the book and in this roundtable; whether The Family is a religious or a political movement; “a political theology”?

Randy wrote that: “The author parses this group as a political movement, but that scheme… doesn’t hold. What if he looked at The Family as a religious movement instead, as I think it is?”

Jeff just said of the media: “There’s a sense here in which the media’s paradigm for political and religious ideas is undermining it…” indicating that the media is getting it wrong on this score. What are they getting wrong?

In order to effectively deal with a complex, cellular, indirect, idea-oriented movement like The Family, one must first draw an accurate picture of what they are, how they function and what relationship they have to the landscape in which they operate. Framing The Family as a political conceit when they’re religious, or vice versa, would significantly hamper any efforts to temper their effect.

In the final tally, what is The Family? A political movement? A religious movement? Both? Do these words have meaningful differences in this context?

AB: Can’t I just say that The Family is bad theology and leave it at that?

Well, sorry to have taken a bit of time between the questions. I’ve been thinking about it since Independence Day, and especially after taking a little walk yesterday over to the grave of Frederick Douglass (who penned one of my favorite July 4th remembrances [given on July 5th!], “What to a Slave is the Fourth of July?”).

I don’t think it’s “religious” or “political,” in the sense that both are intertwined so murkily within The Family’s actions and belief system. If members really did take in the words of Jesus literally, then dealing with the Suhartos of the world would be problematic. If they were truly, truly, political (as they seem to behave) then it would be a matter of just backing and creating politicians, right? But its more like a movement—and this movement is about certainty.

Certainty means that Jesus has put the right people in charge, and submission and assistance to them will ensure that God’s Kingdom will eventually come. It is the certainty that American history is a God-centered history, with a purpose at its core. Come what may, right or wrong, the eventual purpose is to have the “Kingdom” with the “King” on earth. And the work (The Family) is important to bringing that certainty about. Because everyone seems to be very certain about what Jesus wants, right?

But there is a nagging question I ask my conservative evangelical friends: what happens when abortion is illegal? What happens when everyone is a Christian on the Supreme Court? What happens when you bring back prayer in schools? What happens when these wretched amoral leaders and avaricious politicians pray? When all of those things come “back,” they say, Jesus has returned for a 1000-year reign; or that it’s what Christians need to do. I tell them that’s the time you have me chained out in the barn and you’ve beaten the black off my back, ’cause that’s your mythic past of wonderfulness. In that past, I am a slave. And you think Jesus is going to have me in a separate heaven to shine your damn shoes, too. Cause what you want, is the past that we had already, and women, immigrants, foreigners, enslaved and free persons of African descent—anyone not a WASP—was out of rights, and luck.

After they look at me, stricken, then chastise me for telling me that’s not how it is (was), I tell them, Oh yeah, that’s how it was. Because that fantasy world existed when Frederick Douglass gave the speech, “What to A Slave is the Fourth of July.” I wonder what Vereide and Coe would say to Douglass, but I think I will close with a quote from the speech, because I’d like to think this is what he would say to them. Insert “Patriot Act” or “Guantanamo” for “Fugitive Slave Law”. They are, unfortunately, on the side of the oppressors.

The fact that the church of our country (with fractional exceptions) does not esteem “the Fugitive Slave Law” as a declaration of war against religious liberty, implies that that church regards religion simply as a form of worship, an empty ceremony, and not a vital principle, requiring active benevolence, justice, love, and good will towards man. It esteems sacrifice above mercy; psalm-singing above right doing; solemn meetings above practical righteousness. A worship that can be conducted by persons who refuse to give shelter to the houseless, to give bread to the hungry, clothing to the naked, and who enjoin obedience to a law forbidding these acts of mercy is a curse, not a blessing to mankind. The Bible addresses all such persons as “scribes, pharisees, hypocrites, who pay tithe of mint, anise, and cummin, and have omitted the weightier matters of the law, judgment, mercy, and faith.” But the church of this country is not only indifferent to the wrongs of the slave, it actually takes sides with the oppressors.

DW: I reread parts of The Family, looking for insight on the religion/politics question, and the answer I found was both and neither. Founder Abraham Vereide’s way of being in the world is based on Jesus, and spills outward into all activities, especially work and politics. To call his vision a religious movement or a political movement misses the point. Rather, it is an orientation to power (also known as Jesus) that uses practical ways to build up and centralize itself.

This type of totalizing perspective seems common to most religious systems. Judaism, Islam, Buddhism and even early Christianity teach a way of life that does not compartmentalize but which seeks power (intentionality, obedience, service and control) for God. The “genius” of the Protestant Revolution was to break apart this unitary system and its divine focus, substituting it with spheres of influence (with greater or lesser degrees of divine penetration depending on your theology) that gave man (gender-specific indeed) his due. That this Protestant notion is completely naturalized among 21st century American knowledge workers is underscored by our use of the term “political Islam,” our hope that all Israelis will accept a secular state, and our belief in church/state separation. It’s also the part of American identity that tends toward hyper-individualism, and results in its schizoid relationship to Christianity. (On the one hand, it’s all about my personal relationship to Jesus but, on the other hand, the centrality of “me” makes self-discipline difficult and temptation deadly.)

We all agreed earlier that the waning of the religious right is a sideshow. Are we decided that The Family is the real deal? I’d argue that its interweaving of capitalism, Christianity and patriotism has penetrated vast swaths of the population and its ideological assumptions orient our media (it’s not Carman who worries me, it’s the New York Times). It’s all good and well to bat around ideas about empire and hegemony, religious motivations and political labels, but at some point we need a strategy. How do we develop a compelling alternative? Can we revivify notions of community, justice, solidarity that also provide spiritual sustenance and a religious vision? What new stories do we tell ourselves?

RB: I very much agree with Anthea’s point about the dangers of constructing a mythic past, for such constructions inevitably place the greatest burdens on those at the margins of society. And to the extent that The Family participates in the fabrication and the perpetuation of such fiction, it does society—not to mention the faith—a disservice. (I retain my objection to Jeff’s overgeneralizations of The Family’s ideology as well as his attempt to see Edwards and Finney as lineal precursors. I am convinced that Finney, in particular, would find the hard-right leanings evident in the religious right and in many individuals associated with The Family utterly reprehensible.)

Anthea also touches on a point that Jeff addresses as well, the matter of theological orientation. Jeff talks about the influence of Rousas John Rushdoony, who as nearly as I can tell was truly crazy but whose ideas have exerted an outsized influence on the religious right and, according to Jeff, on members of The Family. Rushdoony’s Reconstructionism is an extreme form of Calvinist, or Reformed, theology. I’ve been accused of exaggerating the importance of Rushdoony’s ideas on leaders of the religious right—and perhaps I have. But the fact that such leaders genuflect in his direction, as do, apparently, some members of The Family, cannot be taken lightly.

But the larger issue that needs to be addressed somewhere by someone is the relative social ramifications of Reformed thinking and that of its polar opposite in Protestant Christian thought, Arminian (or Finneyite) theology. Donald Dayton has been arguing for years that if you interpret evangelicalism as a species of Reformed theology, you wind up with the religious right. Whereas if you view evangelicalism through the lens of the Holiness-Arminian-Finneyite-Wesleyan tradition, you get a fuller picture of the true ameliorative character of evangelicalism, one that gave us the abolition movement, public education, various peace crusades, the temperance crusade (a progressive cause in the nineteenth century), and the push for equal rights (including voting rights) for women.

It seems clear from Jeff’s book that the general theological orientation of most members of The Family is Reformed. It’s also true that many of the leaders of the religious right claim to be Reformed (most of them aren’t really Calvinists, but they think they are). Is there a strong, or even a necessary, correlation between Reformed theology and political conservativism? Just anecdotally among some of my colleagues in the field of American religious history, I can probably make that case. But I’d love to see someone parse that question a bit more fully.

Finally, Diane’s comments point us to the heart of what I think is the real contribution of Jeff’s book: the ineluctable lure of power, which, among people of faith, is unseemly. Not simply because it’s grasping and tacky, but because it contradicts the example and teachings of Jesus and because it inevitably compromises the integrity of the faith itself. As I’ve been arguing for years now (and I apologize for repeating myself here), faith functions best from the margins of society and not in the councils of power. When you conflate religion with the state, as some members of The Family are prone to do, inevitably it is the faith that suffers. Once people of faith begin lusting after influence, they lose their prophetic voice.

Roger Williams recognized that long ago, and so did Charles Finney.

JS: Randy offers Arminian, “or Finneyite,” theology as an antidote to the fundamentalisms, plural, that I describe in The Family, rapping me on the knuckles for identifying Finney and Edwards as “lineal precursors” to The Family and contemporary fundamentalism. All I can say is: The Cedars, The Family’s headquarters, includes a room named for Edwards, Ted Haggard called himself an Arminian in interviews and his books, and when, before his fall, I asked him to identify his two favorite theologians, he said “Jonathan Edwards and Charles Finney.” Pastor Ted also accepted the label fundamentalist. What, does Randy think I make this stuff up?

Evidently, he does. As Evan Derkacz notes in his introduction to this roundtable, Randy’s response above is actually his second version of “last words” on The Family. The first came in the form of an acidic analysis in The Washington Post seemingly at odds with Randy’s thoughtful response above. Whereas Randy writes here of some contribution I may have made, in the Post he describes me as merely “sophomoric,” accuses me of lying, and urges greater generosity for The Family’s leader, Doug Coe, whom he wrongly identifies as a minister, guilty of little more than modesty. Randy presents no stronger evidence for his assertions than the genteel revelation that he himself once spent some time living in a house run by The Family and didn’t observe anything like what I describe. But whereas Randy will always have his memories, I have notes, articles that have gone through fact checking and legal review, and tens of thousands of xeroxed documents from The Family’s archive at the Billy Graham Center.

Ah, sour grapes! Yes, I got ’em. Not so much because Randy radically misrepresented my arguments in the Post, where I can’t respond, while offering far more nuanced arguments of his own only in this smaller and more scholarly roundtable, but because such a dichotomy represents exactly the scholarly/popular divide that allows The Family to slip between the cracks. Amongst scholars, he makes arguments that invite engagement. In the public square, he issues proclamations that do no more than police the borders of respectable knowledge, aka “conventional wisdom.” To wit, from Randy’s response #1, in the Post:

“When he encounters evidence that contradicts his meticulously fabricated schematic, Sharlet glosses over or tries to ignore it. Take, for example, former senators Mark O. Hatfield of Oregon and Harold E. Hughes of Iowa, who had close ties with Coe; both were distinguished liberals with little patience for dictators.”

The logic here seems to be that Hatfield and Hughes could not possibly have been involved with dictators because they were liberals; and they were liberals because they could not possibly have been involved with dictators. So much for the evidence that they were both liberal and supportive of dictators (as noted above, Hatfield lobbied for a special prayer breakfast in America for the Indonesian dictator Suharto; Hughes flew to the Philippines to fete Ferdinand Marcos in a presidential prayer breakfast organized by The Family). I neither gloss over nor ignore that apparent paradox but rather place at the center of my argument about the Cold War convergence of multiple strands of American fundamentalism and imperialism. But Randy, known as a “distinguished liberal” himself, as well as a compelling critic of the populist Christian Right, apparently wasn’t kidding when he wrote “the temptation to understand all this through the lens of partisan politics is almost irresistible.” Indeed, he succumbs, dividing the world between good liberals and “tacky” conservatives, the distinguished and the sophomoric. When confronted by evidence that these categories are not so hard and fast as his inner social scientist would like, he falls back on a rhetoric that constructs a reasonable middle by dismissing all to its left and its right as paranoid. For Randy, the center always holds.

But the center is an assertion, not a fact; an etiquette, not a place. Its code, its theology, is most fully embodied in Americanized Arminianism—a Protestant tradition of good works and propriety, “distinguished liberals” and polite realpolitik. “Arminian moralism,” notes historian Charles Sellers in his study of Finney’s age, The Market Revolution, “sanctioned competitive individualism and the market’s rewards of wealth and status.” It did not endorse explicit greed; rather, those whom the market rewarded—Finney’s financial backers, the “judges and lawyers and educated men” Finney boasted of as converts—were to use their good fortune to improve the masses, a trickle-down religion that found an echo in The Family’s belief that God operates through “key men” placed by Him in positions of power, whether in business or government.

“Finney,” writes Randy, “who devoted his entire career to improving the lot of those at the margins of society, would be appalled by the kind of elitist, anti-union sentiments that Sharlet attributes to The Family.” Randy seems unfamiliar with the concept of paternalism, sometimes resented by “those at the margins of society”—in Finney’s time, the poor and the working classes, who comprised the majority of society. As Paul E. Johnson shows us in his classic study of Finney and evangelical revival in Rochester, New York, Finney’s closest allies were not those at the margins of society but their employers, the Christian businessmen genuinely troubled by drunkenness and Sabbath-breaking and yet incapable of imagining that workers might prefer their own solidarity to the fellowship of an evangelicalism paid for and proselytized by the upper middle class. * * * Diane writes: “We all agreed earlier that the waning of religious right is a sideshow… How do we develop a compelling alternative? Can we revivify notions of community, justice, solidarity that also provide spiritual sustenance and a religious vision? What new stories do we tell ourselves?”

Is Arminianism really the best story we can come up with? To the elite fundamentalism of The Family, a religion of the status quo, we should respond with—more noblesse oblige? And to the raw democratic challenge of populist fundamentalism, the modern heirs of the men and women who first rebelled against Darwin not out of blind obedience to authority but rather resentment of Darwin’s early champions—eugenicists, sterilizers, do-gooders—we should respond with—more noblesse oblige? A government of the best and the brightest, the myth of meritocracy, a carrot for strivers and the bludgeon or the dole, depending on which party is in power, for those who’ll never make the cut? Thin gruel.

Randy writes: “faith functions best from the margins of society and not in the councils of power. When you conflate religion with the state, as some members of The Family are prone to do, inevitably it is the faith that suffers.” This statement strikes me as rather high-minded. The faith of the powerful, the faith of The Family, is real, and it is dangerous—not to those who hold it, but to those who suffer because of it. It’s dangerous precisely because it’s so easily overlooked, so easily declared nothing but posturing, a veneer for politics. But empire, what political theorists Antonio Negri and Michael Hardt describe “not as a historical regime originating in conquest, but rather as an order that effectively suspends history and thereby fixes the existing state of affairs for eternity” requires more than politics. It requires belief. There are a very few political figures who can truly practice realpolitik—Cheney, perhaps, and Kissinger. When we look at the private papers of the rest, when we ask them about their gods, we discover theology; theodicy; justification.

What do we call it when Senator Sam Brownback, a Family member and Colson protégé, helps send American dollars to Central Asian dictators to buy access to those markets for American companies because, he explains, capitalism and democracy go together, and the gospel follows? Is that religion, or politics? Does it matter to the subjects of those dictators? Or, to put that question in the terms Anthea reminds us of, “What to a Slave is the Fourth of July?”

Anthea, and Frederick Douglass, point us in the direction of the strategies Diane calls for. Anthea gives us a response to conservatives who long for a “return” to some past they imagine to be more decent, more honest, maybe more Christian: “In that past,” writes Anthea, “I am a slave.” This leads to Strategy #1: History. Not watered-down history, not polite history, not the kind of “progressive history” that maintains that despite the sins of the past we’re inching toward Bethlehem, but brutal, obsessive, investigative history, one story after another, each unraveling the last.

Frederick Douglass, meanwhile, reminds us of the chief pitfall of liberalism, complacency. It can be seductive, especially when it comes cloaked in proclamations of harmony and unity. That was Family founder Abraham Vereide’s great strategic realization: a friend to fascists, he was never a hater himself, and he realized that his movement would advance not by pounding pulpits but by “making friends,” as he liked to say; by gently insisting that we’re all in this together even as he pursued “Worldwide Spiritual Offensive,” a “World War III,” in his imagination. Vereide knew which side he was on; we should as well. So, strategy #2: Know your enemy, and know that your enemy really is your enemy. Love them if you must, but never forget that we are not, in fact, all on the same side.

Defenders of the status quo, liberal as well as conservative, urge civility as an unbreakable code and preach common ground as a common good, as if the oppressed will benefit by toning down their demands in order to stand on the same patch of land as the powerful. Vereide called this “reconciliation,” a beautiful word turned ugly in the mouths of the powerful and the paternalistic. One of his favorite examples? A labor leader on bended knee before a boss, asking forgiveness for his rebellion. One of Chuck Colson’s [examples]? Eldridge Cleaver, a founder of the Black Panthers, broken in spirit, black power abandoned, on his knees, in a Family prayer cell with Colson and Harold Hughes—bipartisanship!—and Tommy Tarrant, a former Klansman in prison for bombing a Jewish family. Cleaver, Colson told Pat Robertson on “The 700 Club,” was reconciled.

Which brings me in closing back to the quote with which Religion Dispatches began this final round: “That which I found I could not change or affect in a political or managerial way,” Colson wrote of the uses to which he put his religion, “I found could be changed by the force of a personal relationship that men develop in a common bond to Christ.”

If we call that politics by another name, we’ll never be able to explain why so many prisoners—Colson leads the largest prison ministry in the world, an evangelical program he described to me as locked in combat with secularism and Islam—embrace it without resorting to that old cop-out of “false consciousness,” radicalism’s version of paternalism. But if we call it religion, we miss the continuity of Colson’s political goals. The alternative to this apparent choice between ignorance and amnesia is not an appeal to the common good nor a revival of liberal rectitude but rather a re-narrated past—history as rebuttal to reconciliation— and a more antagonistic present, a politics of edges too rough to be smoothed into the status quo.

Randy, in closing, reminds us of the “prophetic voice.” Let’s make it democratic; let’s make it plural. How will we recognize these voices? I find most persuasive Cornel West’s description of prophecy as rooted in suffering, in the blues. “‘The blues,’” West quotes Ralph Ellison, “‘is an impulse to keep the painful details and episodes of a brutal experience alive in one’s aching consciousness, to finger its jagged grain, and to transcend it, not by the consolation of philosophy but by squeezing from it a near-tragic, near-comic lyricism.’”